Blog

Devon Wilson is a Research Assistant at Project Zero, where he works on the Out of Eden Learn project and the ID Global project. This blog post reflects work that Devon undertook in collaboration with Carrie James.

Author’s note: In this piece, I describe insights from a series of interviews with educators who creatively utilize the Dialogue Toolkit to support thoughtful dialogue amongst students. I identify six powerful teacher moves and provide more details about how these moves are enacted in these teachers’ classrooms and contexts. For a distilled version of the six powerful teacher moves, click here.

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

It can be easy for students to like something on social media or digital learning platforms, but how can we encourage students to expand their repertoire of skills for online commenting and exchange?

The Dialogue Toolkit (DTK) was designed to promote thoughtful commenting and meaningful discussions in online learning communities (including Out of Eden Learn (OOEL), the digital exchange program for which the DTK was originally designed). By highlighting specific moves that students can use in their comments, the DTK aims to slow down the process of responding and exchanging ideas with online peers. It also helps direct students’ thinking, and ideas for comments, in different directions in order to support a higher quality of exchange and mutual understanding between students.

Even with the Dialogue Toolkit as a resource, without teacher support, many students may still rely primarily on “liking” an online post or providing quick comments that do not move the conversation forward. The following strategies for enhancing student dialogue, using and extending the Dialogue Toolkit, emerged from a series of interviews with educators. In these teacher’s classrooms, we observed students using the Dialogue Toolkit effectively and seeing the value of using the Toolkit’s moves to support thoughtful dialogue. Specifically, in these teacher’s classrooms, we observed one or more of the following moves:

1. Model and Practice Different Dialogue Toolkit Moves

2. Reinforce Physical & Electronic Presence of the Toolkit

3. Coach and Provide Feedback on an Individual Basis

4. Connect to In-Person Communication Strategies

5. Use DTK Moves in Delivering Feedback on Student Work

6. Discuss the Purpose and Value of Thoughtful Dialogue in Digital Exchange and Beyond

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

1. Model and Practice Different Dialogue Toolkit Moves

In Angelia Crouch’s Middle School World History class at St Joseph Catholic School, an emphasis on dialogue moves starts right away, in the initial footsteps (learning experiences) of their OOEL learning journey. After giving students an opportunity to look closely at the Dialogue Toolkit, she guides them in looking together at images and text from a few sample posts, asking them to consider some of the ways they could respond.

Sample Photographs from OOEL students Neighborhood Walk Posts

As she guides students in looking closely at a single post, she asks questions such as:

“What is one thing that we can notice about these pictures that stands out to you?”

“Can you tell from this picture what this student really wanted us to know? Based on how they’re taking the picture?”

“What questions does this raise for you?”

In addition to looking and thinking about a few posts together, students have the opportunity to look back at the Dialogue Toolkit and consider the different moves and ways to engage with other students’ posts. Later on, in the course of digital exchange, we see Angela’s 6th grade students continuing to comment in ways similar to the shared discussion questions described above.

Looking closely and sharing details from other students’ posts:

“I love your map. I like how much color you put into it and all of the trees” (Dog Lord)

“I noticed all of the foot prints in the snow” (Kathleen)

“I noticed, when you look out of the window, you can see amazing views.

Hello again! I hope you enjoyed my previous post in this two-part series, where I discussed how I came to explore students’ diagrams from the Connecting Everyday Objects to Bigger Systems footstep in the Out of Eden Learn (OOEL) curriculum and the three different areas of focus I found in student work. In this post, I share another set of findings as well as some questions and implications raised by my explorations in general.

How Do Students Represent Relationships between Elements in a System?

In addition to differences in what students focused on when diagramming a system connected to their chosen object, I noticed that the elements of the systems that students diagrammed fell along a spectrum in terms of the way relationships were represented. Students’ system diagrams ranged from not having any identified elements (and thus not really appearing to be diagrams) to having elements that were not clearly related to each other, having elements connected in a unidirectional linear relationship, and, finally, having interrelated elements with multidirectional relationships. The student diagrams below are examples of this spectrum.

In the first diagram below, the student included multiple images, but it is not clear how they are related or whether they are elements of a system:

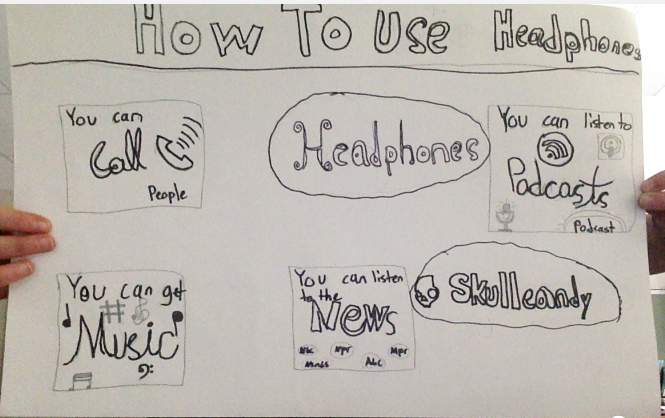

In the next diagram, the student identified a possible system (the use of headphones), but it’s not clear how the different parts relate to each other:

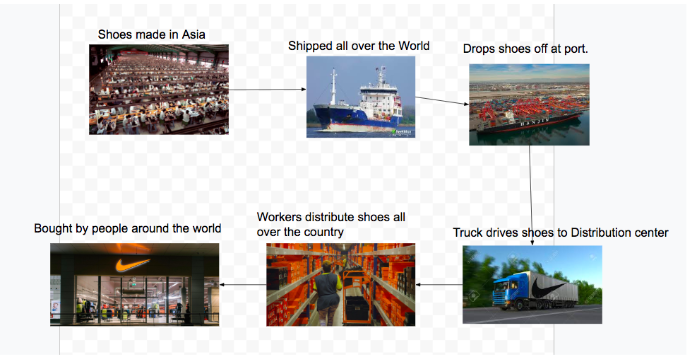

As I discussed in the previous post, many students depicted a process, such as manufacturing or distribution, as their system. Their diagrams often depicted unidirectional, linear relationships between steps in the process, such as the following:

Finally, just a few students went beyond a simple flow of steps or unidirectional relationships between parts of their system. These students’ diagrams showed system elements as interrelated with each other, demonstrating greater complexity in the system, like this example:

Puzzles & Ideas Going Forward

As I noticed these different themes and approaches in students’ work, the researcher in me began considering: What might be the source/s of these differences? I wondered whether variations in the focus of students’ diagrams or in how students illustrated the relationships between system parts might be related to their development (for example, do older students demonstrate a more sophisticated understanding of the complex relationships between parts in a system or more frequently recognize the human agency in systems?) or related to their classroom (for example, might teacher instructions or school culture play a role in diagram focus and relationship visualization?). Interestingly, I did not anecdotally notice any associations between students’ age or classroom and the focus of their system diagram or how they represented the relationships between system elements. This may suggest that these diagram differences are more related to variation across individual students, but these possible associations are something I hope to explore more systematically in the future.

Although these two sets of observations on student diagrams’ focus and relationship of parts seem logical and resonated with my OOEL team members, who have more experience with the student work, they aren’t the last word on what’s happening for students in the Connecting Everyday Objects to Bigger Systems footstep. I only looked at the work of students in two walking party groups during one year, and they may not be representative of all students who might consider a system through the lens of an object or who engage in this particular Out of Eden Learn footstep.

Even if these categories do stand, they raise just as many new questions for me:

- What other contextual information would be useful to better understand the thinking behind students’ diagrams?

- Why do some students not identify the people involved in a process or other system (especially after the previous two footsteps in the Core Learning Journey 2 curriculum invited them to explore their own and others’ connections to objects and bigger ideas)?

- Why do some students illustrate more explicit, directional, or multi-directional relationships between the parts of a system?

- How important is it for students to identify their own role in a system, and how might we support them in doing so?

- How might we encourage students to see the elements in systems as more interconnected, rather than strictly linear?

- What benefits or drawbacks may there be in having students draw the diagrams themselves compared to having them assemble existing images from other sources?

- How might students’ earlier interactions with peers on the OOEL platform influence what they post for this footstep?

- What is the role of peer dialogue in furthering students’ thinking about their selected object and system/s?

Despite these questions, there are some initial ideas for practice that my observations might suggest, whether students are exploring systems through objects on the OOEL platform or in other contexts:

- Consider people: Invite students to think about who makes each element of the system possible

- Insert yourself: Explicitly prompt students to consider where they fit into the system that they’re exploring

- Look further: Ask students to consider what people or communities aren’t involved in a system – and why that might be

- Connect parts: Encourage students to consider how each element of a system relates to each other element, in addition to how linear elements may be linked in a sequence

- Think macro: Have students diagram how different systems themselves are related

- Think micro: Have students drill down to consider an object within one element of their system diagram and what systems/processes may be related to that element

These are simply some preliminary wonders and thoughts that this exploration of the fascinating student work in the Connecting Everyday Objects to Bigger Systems footstep raised for me. I look forward to hopefully reviewing more student posts, potentially developing a more formal tool/kit for supporting systems thinking through objects, as well as hearing from teachers about what may or may not resonate about these concepts! In these times of rapid change, social divisions, increasing globalization, unequal access to resources, and other challenges, it feels especially important to offer learners tools and opportunities to make sense of the systems around them – and to consider how they may play a role in those systems.

For some other resources from Project Zero on supporting students’ systems thinking, check out the thinking routines from the Agency by Design project and the ‘Art to Systems and Back’ tool from the Art as Civic Commons project.

I’m a relatively new addition to the Out of Eden Learn (OOEL) team, although I’ve been working at Project Zero for almost a decade. Part of my background is in museum education, so I’m particularly interested in learning experiences that incorporate objects, whether works of art on a gallery wall, natural history specimens under glass, fish in an aquarium, or commonplace items that surround us. I’ve thus been especially curious about elements of the OOEL curriculum that invite students to explore objects around them, like the Connecting Everyday Objects to Bigger Systems footstep in the Core Learning Journey 2 curriculum. I recently set out to see what was happening in that footstep and how students might be exploring systems using objects as inspiration. In this post, I share a bit about my process and one set of findings, and in the next post, I’ll share a second set of findings as well as some overall questions and implications.

Exploring Student Work in a Footstep of their Learning Journey

The Connecting Everyday Objects to Bigger Systems footstep, like most OOEL activities, is framed quite broadly to allow space for students to explore their own interests. However, as the name of the Core Learning Journey: The Past and the Global suggests, its intent is to help students recognize that everyday objects can be seen as part of a web of larger, often global, connections. The footstep (which is also available as a stand-alone activity) also engages students in all three of the overarching OOEL learning goals: students slow down to look closely at an object, they consider the stories it might be a part of, and they make connections between the object and the wider world.

The footstep invites students “to look closely at an everyday object and then make connections between what you notice and bigger systems that the object might be part of.” They are prompted to engage in a sequence of activities to explore an object and related systems: they select an object, look closely and slowly at it, write questions they have about it, consider different systems that could relate to it, and draw a diagram of the different parts of one relevant system. Students are then asked to share their diagram with peers in their walking party, with a picture of their chosen object if possible. Many students also posted text explaining their diagram, and some only posted a written description, without any visual diagram or object image.

I looked at student discussion board posts from this footstep that were shared on the OOEL online platform from two 2019 walking parties (groups of classrooms with similarly aged students from different countries around the world). The 2021 posts were still in progress as I began, and the 2020 work was disrupted, like so much else, by COVID-19, so I went back to 2019 posts to get a sense of what might be more typical student work for this particular footstep. I selected two walking parties with students in diverse geographical locations that had students aged 10-14, although students of other ages also engage with this material. There were just over 90 students who posted work for this footstep across the two walking parties.

I started looking through students’ posts, including their written descriptions and diagram images, with some possible questions in mind:

- What kind of objects do students select?

- What systems do students connect objects to?

- Do students discuss their rationale for selecting the object, and, if so, what are the rationales?

- What kinds of questions do students ask about the object?

- What objects/systems seem to spark the most student dialogue?

While the answers to these questions may be interesting and generative, two unexpected patterns really stood out to me as I began investigating students’ work. These patterns raised questions that I hadn’t gone into the exploration even considering: 1. What did students focus on when diagramming their object-based system? and 2. How were students representing the relationships between system elements in their diagrams? Below, I discuss my observations around the first question, and the next blog post will explore the second question.

What Did Students Focus on When Diagramming Their Object-Based System?

I noticed that the focus of students’ work in their systems diagrams generally fell into one of three categories: parts of an item, a process without human involvement, and people’s involvement in a process.

Parts: Although this was not an especially common area of focus, a few students illustrated the object itself as a system, identifying different parts of the object as the elements of the system. Students focused on the parts of both natural objects, like this date plant:

as well as human-created objects, like this soccer ball:

Processes: More commonly, students focused on a process in their diagram. This was most often the process of manufacturing the selected object. Some of these diagrams illustrated the process without explicitly incorporating people who might be involved in particular elements. Such diagrams visualized, for example, various parts in the process of transforming raw materials into a finished product, such as this diagram showing steps in the process of transforming sheep’s wool into a sweater:

Other students illustrated the steps in the distribution or sale of their chosen object, like this system of car transport to a dealer:

People: Students who created system diagrams of a process frequently incorporated human contributions to the system, unlike the examples illustrated above. Some students just identified people as an end user or consumer of the object, like the student below:

Other students identified people involved in the creation, as well as the consumption, of an object, like the bracelet maker and buyer illustrated below:

Although it wasn’t something I went into my preliminary investigation of student work considering, it was interesting to observe students’ focus on the parts of an item, a process without human involvement, or process with people’s contributions in their object-based system diagrams. In the next post, I’ll discuss the second set of findings from my exploration.

Note: 1. Students select anonymous usernames to represent themselves to peers on the OOEL online platform, and those usernames are provided here when attributing work to students.

In this blog post, I describe my journey with Out of Eden Learn as an educator in a learning context called The Aspiring Phoenix Foundation (TAPF), an Acton Academy, where “studios” replace classrooms and learner-driven environments are core to our mission. Out of Eden Learn (OOEL) offered new opportunities and a new venue for the children to lead their learning. While the context in which I work is unique, our practices and journey with OOEL are relevant to more traditional classrooms and schools.

When a close friend from college, who is also an educator and life-long learner, recommended OOEL, I was eager to check it out. I was so pleased that the OOEL materials and resources were set out in such a user-friendly way. I was certain that our learners would be able to take the lead before the end of the year. As a guide, my role is to set the stage for the children’s learning, give them the tools and resources to accomplish the objectives, and stand aside. Each day, we have “Launches” in the morning and after lunch. The aim is to tell a story, pose a question, or make a statement and allow time for Socratic debate. There are no “right” or “wrong” answers.

In our Elementary Studio (ES), 7 learners between 8-12 years old participated in OOEL for their Civilization Time, twice a week for 45-60-minute slots. We function as a multi-age studio, rather than dividing the children by age and grade level. Peer-to-peer learning is such a powerful tool, given each of us have various degrees of strengths and weaknesses. In my experience, age hasn’t been the defining factor of mastery or maturity; rather, intrinsic curiosity that is allowed to follow its path normally leads to even more opportunities to learn. On our campus, our learners immerse themselves in their roles as an anthropologists /scientists /investigators/authors/photographer, depending on the learning adventure and challenge. In our program, our goal is for curious investigation and deep exploration to become part of the joyous cycle of a lifelong learning.

The students were intrigued with the idea of doing “The Present and the Local” OOEL learning journey, and decided to undertake it. In the beginning, we watched the videos together, discussed together the target Footstep for the day, and then they organized themselves to work in pairs or small groups, occasionally someone would work alone for a bit, then come back to join after they accomplished their personal goal. The Dialogue Toolkit (DTK) easily integrated into the learners’ everyday language since it helped them follow the Rules of Engagement, which are set by the learners at TAPF at the beginning of the year. The rules include stating “I agree/I disagree with… because…”, linking their comment to the previous statement, and not interrupting the person who is speaking. The children hold each other accountable according to their “Studio Contract” that functions as their constitution. They wrote the document themselves and they can adapt it as they see necessary to govern their Studio. Everyone had access to a digital copy of the Dialogue Toolkit in their online portfolio, and a large poster of it was prominently displayed in a central location for easy reference. Frequently, I witnessed the children looking at the poster or finding it in their portfolio. I saw them use phrases from the Dialogue Toolkit such as “I was surprised by…” and “Could you tell me more about…?”, when they were asking each other for clarifications during group discussions after watching the videos together in Part 1 and when extending the dialogue through replies to online posts. The children actively listened to their peers and new friends from their “walking party” while strengthening their interpersonal communication skills.

As they participated in OOEL Core Learning Journey 1: The Present and the Local, I observed how the learners became engaged with the content and how it spurred further inquiry and investigations. It was thrilling to watch them dive into a topic and whole-heartedly explore it. The Neighborhood Walks footstep was a Studio favorite. The children were clearly happy to be outdoors and doing something exciting. They enjoyed investigating their surroundings while looking closely at the neighborhood for “evidence” to answer the questions from OOEL. As a group, they clearly were enjoying themselves: themselves in discussions about geography, current events, and, in doing so, developed their skills of looking slowly and listening actively.

To wrap up each Civilization Time, learners shared their reflections as a whole group, offering feedback, and highlighting strategies that had worked for them to keep on track with their daily and weekly goals. When I began asking who would like to lead the closing reflection after these sessions, many eager volunteers emerged. It was time to let them begin taking over and closing reflection, which turned out to be a simple process it was the most similar to their launch process, and Rules of Engagement with DTK support. For example, when the Civ Time Leader gathered the group at the end of a time-block, they would pose a general reflection question, like “What was the most interesting thing you discovered today when looking closely? What is your best “good question?”, then proceeded to moderate the conversation as they do in their regular discussions, weaving in DTK language and strategies to connect, notice, and share.

When we embarked on our second OOEL adventure, an Introduction to Planetary Health, I asked for a volunteer to lead Step 1 and someone to lead the Closing Reflection. There were several volunteers and as per our custom, a vote was held to decide who would be leading Step 1 and who would wrap up our OOEL Time. I took my lead from the learners; they gradually took over until they were running it all. I am present on our Neighborhood Walks to ensure everyone’s safety and security while exploring off-campus; otherwise, the learners are running the show. They schedule when we go on Neighborhood Walks, and they have lively discussions as we walk around our community.

In the future, I will continue to stand back and allow the learners to lead OOEL. It builds their self-confidence, encourages them to put their theoretical knowledge in practice, and helps them reflect on how history and the present intersect in their lives. By taking ownership of their education, the children deepen their understanding of the topics and take meaningful steps towards their life-long learning journey. Using OOEL with an increasing sense of autonomy for students has supported many moments that will keep them curious about the world around them, encourage them to invent, innovate and create, then pursue how to “fail forward” the next time to constantly seek to improve themselves and the world around them. Although my learning context may be unique, educators in any context can have their learners take the lead with OOEL and beyond.

The new COVID-19 reality has given us some hiccups for sure, however, I’m proud of our learners and their resilience. When we shifted from on-campus meetings to completely virtual interactions in mid-March, the transition was as smooth as it could be considering it happened over the weekend. Our plan is to continue with our OOEL Journeys. It’s a great opportunity to interact with other learners across the globe and exchange stories about how they’ve been impacted too. Overall, our little community has been flexible, continues to adapt according to updated COVID-19 guidelines, and is finding its own way to thrive.

——————————————————————————————————————–Alexis Cole is co-founder, learning arc designer, and guide at The Aspiring Phoenix Foundation (formerly Liberty Leadership), an Acton Academy affiliate in Bel Air, Maryland. She holds an MA in Curriculum and Instruction from Arizona State University and BA in Sociology from Taylor University. When she isn’t working on changing mindsets about education, she loves reading, cooking, gardening, crafts, and music. Travel is usually on the top of the list, but it has been quarantined for the moment.

This piece was co-authored by Liz Dawes Duraisingh, Sheya, and Nir Aish from the Out of Eden Learn team.

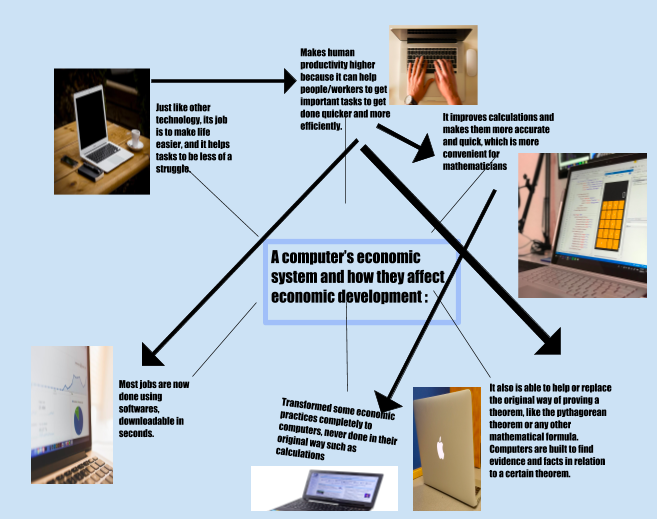

Overgeneralization. Overconfidence. Othering. These three overlapping behaviors make up the Three O’s.

- Overgeneralization: making comments about whole groups of people as if everyone’s experience or perspective were the same.

- Overconfidence: overestimating how much one knows or understands about a phenomenon or group of people, leading to a lack of curiosity or appropriate humility about the limits of one’s knowledge.

- Othering: implicitly or explicitly conveying that one does not consider people from another group to be quite one’s equal, perhaps through a dismissive or overly pitying tone.

This framework emerged from a close examination of what students were generally learning about culture(s) on the Out of Eden Learn platform, as well as what they were learning more specifically about migration from the Stories of Human Migration curriculum. Data from these studies (including student work, dialogue, surveys, and interviews) displayed for the most part highly positive learning outcomes: for example, showing great interest in and concern for one another’s stories; developing more nuanced understandings about culture(s) and/or migration; and exhibiting greater self-awareness regarding their own identities and perspectives on the world. However, we also identified some subtle and occasionally not-so-subtle behaviors that felt less aligned with the underlying philosophy and intent of Out of Eden Learn: the Three O’s of overgeneralization, overconfidence, and othering (read more about these promises and pitfalls).

When we started to talk about these opportunities and challenges, educators unsurprisingly showed interest in the Three O’s: trying to help young people understand and navigate the cultural complexities of our contemporary world can be challenging and complicated. We wondered what further resources we could develop for students and educators and whether explicitly naming the Three O’s upfront would be helpful. During a recent OOEL launch, we piloted a video that attempted to explain the Three O’s to students before they engaged on Out of Eden Learn and asked a group of educators to explicitly discuss the Three O’s with their students in class.

Over recent weeks we held informal Zoom-facilitated focus groups—some with students aged 10-13; others with students aged 13-18. The students came from a range of family backgrounds and geographic locations: Adelaide in South Australia; a village in Bihar, India as well as the city of Thane—and in the United States, small towns and big cities in: Massachusetts, Illinois, Connecticut, Wisconsin, New Hampshire, and the Hawaiian island of Hawai`i.

Did students find it useful to have the Three O’s named before interacting with peers living in different contexts to their own? What did each of the Three O’s mean to them? What connections did they make between the Three O’s and other aspects of their life? Have they Three O’d others? Have others Three O’d them? We also separately interviewed teachers to learn from their experiences and perspectives.

What we have been learning reflects the stark realities of our time and offers a good deal of hope. Students expressed a genuine desire and commitment to learn about—and talk about—the Three Os. They shared experiences and observations from their daily lives in ways that indicated multidimensional applications of the Three O’s. In upcoming blog posts we will share their insights along with practical classroom tools we are in the process of developing. We believe these tools and insights might help other students–and indeed all of us–to interpret and navigate our complex world, both on- and offline.

If you are interested in learning more about the Three O’s framework, join OOEL team members for an upcoming two-part Project Zero online virtual workshop on August 10th and 12th.

This post is authored by Devon Wilson and Shari Tishman. Devon Wilson is a research assistant at Project Zero, where he works on the Out of Eden Learn project and the ID Global project. Shari Tishman is a co-director of Out of Eden Learn.

Out of Eden Learn is excited to share a short new video about the Out of Eden Learn learning journey, An Introduction to Planetary Health. The learning journey, developed in collaboration with the Planetary Health Alliance, helps students explore the relationship between environmental change and human health, and the video tells the stories of students and teachers from three different parts of the world who participated in a learning journey together in the fall of 2019. Though the video was completed just days before the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic, it feels especially relevant today.

As communities around the world entered lockdown in early 2020, a consequence observed by environmental researchers was an associated decrease in CO2 levels internationally along with a flourishing of many natural environments due to the reduced presence of humans. At the same time, the disparity of COVID-related health outcomes across communities has led to a dramatic increase in awareness of how local and global environmental conditions contribute to human health outcomes. Many refer to this moment as an opportunity for a “great realization” – a moment to look at ourselves in the mirror and say that we cannot continue on as we previously have. Yet as economies begin to re-open, we already see increases in CO2 and environmental degradation, and most systemic issues affecting human health continue to persist. Indeed, with the loosening of environmental regulations in the name of economic recovery, these issues threaten to become worse.

As we begin to return to classrooms around the world—whether online or in person—we are presented with a fresh set of opportunities to do things differently. The Introduction to Planetary Health learning journey gives students the opportunity to actively explore the intersection between environmental systems and human health—in their own communities and around the world. Like all Out of Eden Learn learning journeys, students take walks in their own neighborhoods, investigate themes that have both local and global relevance, and share stories that matter to them with their online peers. Also like all Out of Eden Learn offerings, the learning journey is entirely free. It takes about 8-10 weeks to complete, and it can be used in online, in-person, or multimodal classrooms. The curriculum can be viewed on the Out of Eden Learn website. The next round of OOEL planetary health learning journeys launch in September and October. If you’d like more information or are interested in signing up, contact us at learn@outofedenwalk.com. In the meantime, we hope you enjoy the video!

Greetings to our Out of Eden Learn Community and other readers of this blog,

We have been thinking about our community members in different places and contexts at this extraordinary time.

As you know, the Out of Eden Learn team is physically situated in the United States, where recent and ongoing events connected to police brutality and racial injustice have reverberated around the world. We recognize the importance of speaking out in solidarity with communities of color—and in particular, the African American community within the US. We did not rush to put out a statement about our values and support for the wave of protests and what feels like a real opportunity for social and political change. As a predominantly white-presenting team situated within a predominantly white research organization, we’ve been focusing our team’s energies on listening rather than speaking, while individually participating in local Black Lives Matter protest events and other advocacy. We’ve also shifted some of the ways we use our social media and have been sharing posts from trusted organizations that more squarely address matters of social and racial justice. It now feels time to open up a more direct conversation with our community.

We believe that our collective work is as relevant as ever at this time—namely, breaking down barriers among young people and encouraging them to learn thoughtfully both with and from one another by slowing down, sharing stories, and making connections. During the past several weeks, for example, we have been conducting virtual focus groups with young people who have been working with our Three O’s framework of overgeneralization, overconfidence, and othering, which supports young people to both reflectively and critically engage with the world—online, in person, when reading the news, etc. Students’ thoughtful responses to our questions reveal that they are finding this framework to be a salient and powerful tool for interpreting and navigating the fraught and complicated world in which we all live. We invite you to scroll through some of their comments in the gallery below, and we look forward to sharing more about this work with you soon.

We have also been learning from educators about best practices for using our Dialogue Toolkit in order to promote thoughtful online and in-person interactions, including among youth who would not ordinarily encounter one another or who know little about each other’s lives. And we have been working on a video that captures what students have been learning about the interdependency of systems related to environmental and human health via our Planetary Health curriculum. We will share these new resources with you soon.

Nevertheless, while we believe all this work to be relevant and worthwhile, there are some genuine puzzles associated with doing international work focused on intercultural exchange across very different settings. Some questions on our mind include: Is OOEL paying too little attention to global inequities, including ones related to racial injustice? Is the project effectively upholding the status quo by not directly promoting activism or more critical debate? Because of the pseudonymous nature of the platform—and the extremely limited sharing of demographic information (e.g. race, gender, etc.)—are OOEL students and teachers steering clear of potentially uncomfortable and complicated, yet ultimately important conversations? As a research team, we recognize that we do not fully understand the specific learning experiences of students who experience various kinds of marginalization in their daily lives, nor have we persistently asked how we might serve them differently or better. Given the composition and geographic location of our research team, we undoubtedly have blindspots and biases in the most fundamental ways in which we develop the program and conduct our research.

As we reflect on what we need to do both in the short term and long term to improve our work, we recognize that we need our community’s help. One first step will be to send out a short survey to our educators in the coming days. The survey will ask the following four questions. We invite you to consider them now, and we warmly—and humbly—look forward to your survey responses. Stay tuned for an email with the link to the survey.

- Consider one or more students in your classroom who might experience some type of marginalization and/or inequities—perhaps for different reasons, such as racial-, ethnic- or gender-based marginalization or inequities due to cognitive or physical differences. How, if at all, are they already experiencing safety and inclusivity on OOEL? For example, are there specific footsteps or activities that work particularly well for these students?

- What additional resources or strategies are you using to help support these students to participate in OOEL?

- How could the OOEL program be more inclusive for students who experience marginalization or inequity in their daily lives? How might specific features of our program, platform, or curricula be modified to better support these students?

- Some aspects of the OOEL curriculum encourage students to explore connections between their everyday lives and bigger systems. Are there specific ways that you think OOEL already helps students explore how systemic racism or local and/or global systems that promote different kinds of injustices such as economic, health, or environmental injustices?

- Would you like OOEL activities to do more to help students delve deeply into how local and global social and economic systems work, and how students themselves might be connected to such systems? If so, what would you like to see? What ideas would you like to share with us?

If anyone reading this blog would like to leave a comment or email us at learn@outofedenwalk.com, we would welcome your thoughts. With resolve, intentionality, and humility, we hope to take the necessary steps to move onward and upward together.

With love,

The Out of Eden Learn Team

Morgan Nixon, an international ELL educator and student in the Technology in Education program at the Harvard Graduate School of Education, is working with the Out of Eden Learn (OOEL) team as a research assistant this semester.

This piece is the third in a series of Learning Landscapes—or weekly distance learning news, strategy, and big-picture updates. Similarly to parts one and two of this series, I have created a slideshow highlighting some key themes I noticed surfacing online this week as educators, administrators, and parents continue to navigate distance learning. While the conversations I am looking closely at are mostly happening within the United States, emerging themes should be relevant to readers around the world. This week’s ‘winding words’ are: the future of learning, technology: digital divide, technology: new opportunities, and instructional approaches. You might notice that accompanying each of the key themes in this week’s slides are a set of reflection prompts for readers to consider as they explore the featured resources. We invite you to share some of your reflections in the comment section below. I hope you find this week’s online learning landscape helpful.

Morgan Nixon, an international ELL educator and student in the Technology in Education program at the Harvard Graduate School of Education, is working with the Out of Eden Learn (OOEL) team as a research assistant this semester.

This piece follows up on the one I shared last week. I have taken the time to synthesize some key themes I saw coming up online this week, as educators continue to navigate—and adapt to—the new reality of distance learning. While I’ve focused on what is happening within the United States, many of the emerging themes should be relevant to readers from around the world: this week’s ‘winding words’ are flexibility, basic needs, voice, special needs, and professional development. I hope you find my presentation useful.

Morgan Nixon, an international ELL educator and student in the Technology in Education program at the Harvard Graduate School of Education, is working with the Out of Eden Learn (OOEL) team as a research assistant this semester.

In order to support our educator and learner community, it is important for the OOEL team to follow what is on educators’ and caregivers’ minds during the COVID-19 pandemic. As a research assistant and member of the OOEL team, I have put together this slideshow synthesizing some of the main themes I have been seeing in the media recently.

I hope you will find it useful if you want to know what educators are talking about at this fast-moving time, but do not have the bandwidth or time to follow lots of news feeds.

This January, nineteen students at the Harvard Graduate School of Education spent two weeks immersed in an intensive course on slow looking. The class was taught by OOEL co-director Shari Tishman. Linked in spirit to Out of Eden Learn’s theme of slowing down to observe the world closely, the purpose of the course was to help graduate students explore the connection between slow looking and deep learning.

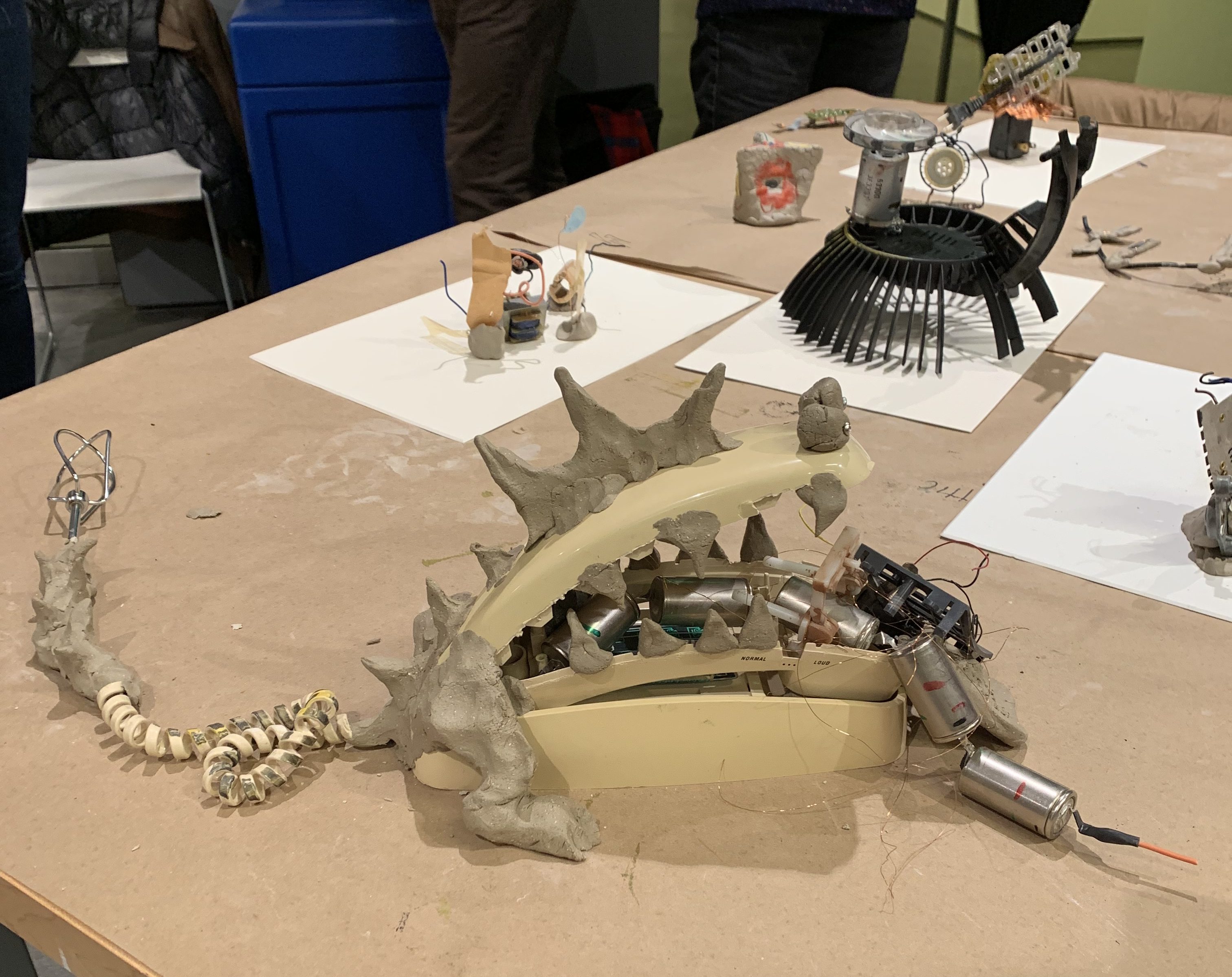

The class activities took place in a variety of locations. One brisk January day was spent outdoors at the Arnold Arboretum, a research center and public park in the Jamaica Plain neighborhood of Boston, where students spent several hours observing a single tree. Another day was spent in a lab at the Harvard Art Museums where students explored the complexity of everyday mechanical objects—first by carefully taking apart a discarded object (broken hair dryer, old phone, electric fan); then by looking at artworks in the museum related to the transformation of everyday objects (Louise Nevelson, David Smith, Willie Cole); and finally by using the parts of the disassembled objects to make assemblages of their own (imagine a large-mouthed monster with the jaws of a phone receiver. The activity was inspired by Project Zero’s Agency by Design project. The website lists several routines and resources available to all educators.

Toward the end of the course, a particularly memorable afternoon unfolded in the cozy interior of Harvard’s Woodberry Poetry Room: Students began by leisurely browsing its beautifully curated collection of poetry, and then settled in to listen slowly and repeatedly to an audio recording of Native American poet Layli Long Soldier reading her poetry aloud. (The Woodberry Poetry Room has an amazing archive of poet audio recordings freely available online in the Listening Booth.)

Toward the end of the course, a particularly memorable afternoon unfolded in the cozy interior of Harvard’s Woodberry Poetry Room: Students began by leisurely browsing its beautifully curated collection of poetry, and then settled in to listen slowly and repeatedly to an audio recording of Native American poet Layli Long Soldier reading her poetry aloud. (The Woodberry Poetry Room has an amazing archive of poet audio recordings freely available online in the Listening Booth.)

Several students in the course were professional educators, and they found that the principles of Out of Eden Learn—slowing down, sharing stories, making connections—resonated with their teaching goals. They left the course excited to introduce slow looking into their own classrooms, and excited to introduce Out of Eden Learn to new audiences. Learn more about the connection between slow looking and deep learning at Usable Knowledge, a digital publication of the Harvard Graduate School of Education.

Charlotte Leech, writer of this piece, co-founded Loka together with Sanat Kumar. Paul Salopek visited Loka on his walk across Northern India, and later met up with the Out of Eden Learn research team there.

Once upon a time there was a Small School with Big Dreams called Loka. It was tucked away along the Punpun river in Bihar, North-India. This school was not just a building with classrooms. It also had a farm, a flower garden, lots of trees, fields to play, pets and was surrounded by endless farming fields, chimneys of brick factories and other small villages. Children learning at Loka lived with their parents in mu d huts or simple unfurnished brick houses. They were mostly small-scale farmers and labourers. At school the children learned many things, not just from books, but also by exploring, creating, imagining, tinkering and through dialogue and reflection. At the end of every school day the children cleaned the campus and made sure to keep their surroundings neat, colourful and beautiful.

d huts or simple unfurnished brick houses. They were mostly small-scale farmers and labourers. At school the children learned many things, not just from books, but also by exploring, creating, imagining, tinkering and through dialogue and reflection. At the end of every school day the children cleaned the campus and made sure to keep their surroundings neat, colourful and beautiful.

One day a man and a woman arrived at the gate of this remote school or free space. The man was Paul Salopek and he was accompanied by his walking partner Bhavita. Paul came walking all the way from Ethiopia and was on his way to Patagonia. He was curious to learn about people and places across the globe and write stories about them to share with the wide world. His long traverse was called ‘Out of Eden Walk’ and brought him to many unknown areas, just like the village where Loka’s school was emerging. Paul spent some days with Loka’s students, and the children were amazed by his journey. “Why walk by foot, why not use a car?” a puzzled student asked. Another wondered what Paul thought about Bihar – a state often depicted in mainstream media as dangerous, corrupt and poor. “Bihar is Beautiful” he said, “and the people are kind and welcoming.” Everybody at Loka was inspired by Paul’s story and presence, and his choice to give up everything and live a different life. Likewise, Loka had touched Paul’s heart, it seemed, as just over a month later he returned with a wonderful group of researchers from Project Zero, a research center at Harvard University. Every couple of years Paul met with them to have a conference about Out of Eden Learn (OOEL), an online platform for cultural exchange the researchers developed which is linked to Paul’s Walk.

One day a man and a woman arrived at the gate of this remote school or free space. The man was Paul Salopek and he was accompanied by his walking partner Bhavita. Paul came walking all the way from Ethiopia and was on his way to Patagonia. He was curious to learn about people and places across the globe and write stories about them to share with the wide world. His long traverse was called ‘Out of Eden Walk’ and brought him to many unknown areas, just like the village where Loka’s school was emerging. Paul spent some days with Loka’s students, and the children were amazed by his journey. “Why walk by foot, why not use a car?” a puzzled student asked. Another wondered what Paul thought about Bihar – a state often depicted in mainstream media as dangerous, corrupt and poor. “Bihar is Beautiful” he said, “and the people are kind and welcoming.” Everybody at Loka was inspired by Paul’s story and presence, and his choice to give up everything and live a different life. Likewise, Loka had touched Paul’s heart, it seemed, as just over a month later he returned with a wonderful group of researchers from Project Zero, a research center at Harvard University. Every couple of years Paul met with them to have a conference about Out of Eden Learn (OOEL), an online platform for cultural exchange the researchers developed which is linked to Paul’s Walk.

During their stay at Loka, three Project Zero researchers, Shari Tishman, Carrie James, and Liz Duraisingh, organised a learning walk.

Students went in pairs on a slow walk and were given the assignment to look closely at something they never looked closely at before.

Students carefully observed:

- An ant walking over their hand.

- A mango tree. Its flowers.

- A mud oven. Good to boil the paddy.

- An eggplant. Its leaves are rough.

- A hole in the field. Possibly a rat’s home. When looking more closely, it looks

- like a well.

After the slow walk, everybody shared their observations and responded to each others’ findings through ‘Appreciations’, ‘Wonders’ and ‘Connections’.

Dinesh: “Somebody wrote about the eggplant; why the flower comes first and not the fruit. That made me wonder.”

Sanatan: “I would like to say something about connection. Many children started their questions with the word ‘why’. That is a connection.”

Liz (researcher): “I want to congratulate your spirit and the way you did the activity. It was very beautiful to see.” (Appreciation)

Everybody at Loka learned a lot during the visit of Paul and the Project Zero team After their departure, students started to participate in OOEL. Imagine children who, until 5 years ago had hardly met anyone outside their locality, were suddenly involved in an international online cultural exchange! Through OOEL, Loka’s students started to slow down, look more closely at their surroundings and share stories of their neighbourhood. They would also respond to stories, photos, videos and other assignments of their ‘walking partners’, children of other schools from all other the world. One of the assignments was to make a neighbourhood map. Some of the maps were created so attentively by Loka’s students that after posting them online, they received many appreciations. One boy from America commented on Dimple’s map: “Could you share some drawing tips?” Dimple never had proper drawing classes, so he explained how he imagined an image that he kept in his mind while drawing. There were also funny moments. For example, when somebody commented on LittiChowkha’s1 introduction post: “Cool that you live in India” and LittiChowkha (1) replied with: “It’s not cool in India, it’s hot!”

After Loka’s students completed their first learning journey, the list of things they said they had learned turned out to be endless. They mentioned practical skills such as improving their English, conducting an interview, making a video and writing an email. They also made observations that were especially interesting coming from children who, until then, had little access to the rest of the world. “Not everywhere is the same as in our village” one student observed. “I learned about the rest of the world by sitting in my school” another added. Other learning points mentioned by students included: how to make a slow walk and observe the big things and small things; looking more deeply; understanding the meaning of the everyday, and learning new words never used before which can make stories more interesting.

This is how a visit from a walking storyteller and a team of highly intelligent people deeply interested in education enhanced the mission of a small school with big dreams. What about the future? Students are eager to start their next OOEL learning journey. Besides that, the school will soon be enriched with a Maker Space through which students will be equipped to uplift their surroundings and–on village scale–create the kind of world we would all wish to live in. And how that world will look? Imagine the Impossible… because that is what children do.

(1) Username created by student especially for OOEL.

-

-

-

-

-

-

Support PZ's Reach