Iwona Piecyk

33 Liceum Ogólnokształcące Dwujęzyczne im. M. Kopernika w Warszawie

Warsaw, Poland

About Iwona Piecyk

My name is Iwona Piecyk, and I live and work in Warsaw, Poland. Originally, I come from the north-west part of Poland called West Pomerania, but I moved to Warsaw to pursue my Master’s Degree in American Studies. I love Warsaw for its atmosphere of opportunity and openness, but I also have a deep passion for travel. So far, I have mostly travelled in Europe and the United States, but I have also ventured to Oman. What fascinates me most is how people live in other countries and what their values are. I always find common ground and shared values with people from different nationalities, which enriches my understanding of the world.

For the past 10 years, I’ve been teaching at the 33 Copernicus Bilingual High School in Warsaw. Our school provides bilingual education in Polish and English through the Polish National Programme, as well as the IB Middle Years Programme (MYP) and IB Diploma Programme (DP). I teach various subjects, including English as a Second Language, IB English Language and Literature, and Theory of Knowledge. I am also responsible for incorporating the Approaches to Teaching and Learning skills into the classroom reality.

One of the greatest joys of teaching is building meaningful relationships with my students and colleagues. I believe that creating a safe and supportive environment is essential for effective learning and helps students become lifelong learners. I cherish the unique qualities that each student brings to the classroom and strive to build on their strengths rather than focusing on what might be lacking. This philosophy not only enriches their learning experience but also fosters a sense of confidence and belonging.

How did you learn about The Good Project lesson plans? What made you interested in using the lesson plans?

I first came across The Good Project in May 2023, while exploring Project Zero Visible Thinking Routines. I stumbled upon an advertisement for The Good Project and was immediately intrigued by its focus on "Good Work." As I read more about the project's objectives, I was fascinated by the emphasis on ethical considerations, responsibility, engagement, and reflection. These themes resonated deeply with the Approaches to Learning Skills we emphasize in the IB Program at my school. The overlap between these skills and those highlighted in The Good Project sparked my enthusiasm to integrate the lesson plans into my teaching. I envisioned how these lessons could complement and enhance our existing curriculum, providing students with invaluable skills for their future.

Tell us about the students with whom you are teaching the lesson plans. In which class are you using them? What makes them a good fit for your learners?

Initially, I planned to teach The Good Project lessons both to my homeroom group of 30 seniors as well as to my 10th graders, a smaller group of 15 students. I believed that the seniors would benefit from examining their value systems and understanding the "3Es" (Excellent, Engaging, Ethical) framework to help them navigate future career choices. However, I quickly realized that my senior students, immersed in the demanding IB Diploma Program, were overwhelmed with coursework and deadlines. They needed our homeroom sessions to focus on well-being, stress management, and study planning techniques. Despite this, I managed to incorporate some lesson plan ideas, such as the value sort activity, which provided great insights into their personal values.

Ultimately, I decided to implement The Good Project lessons with my IB MYP year 10 students. This group was particularly enthusiastic about the project, displaying a keen interest in discussions, debates, and dilemmas. Their active participation and honest reflections made them an ideal fit for the lessons. They engaged with the ethical and reflective aspects of the lessons, often extending discussions beyond class time.

What has been a memorable moment from your teaching of the lesson plans?

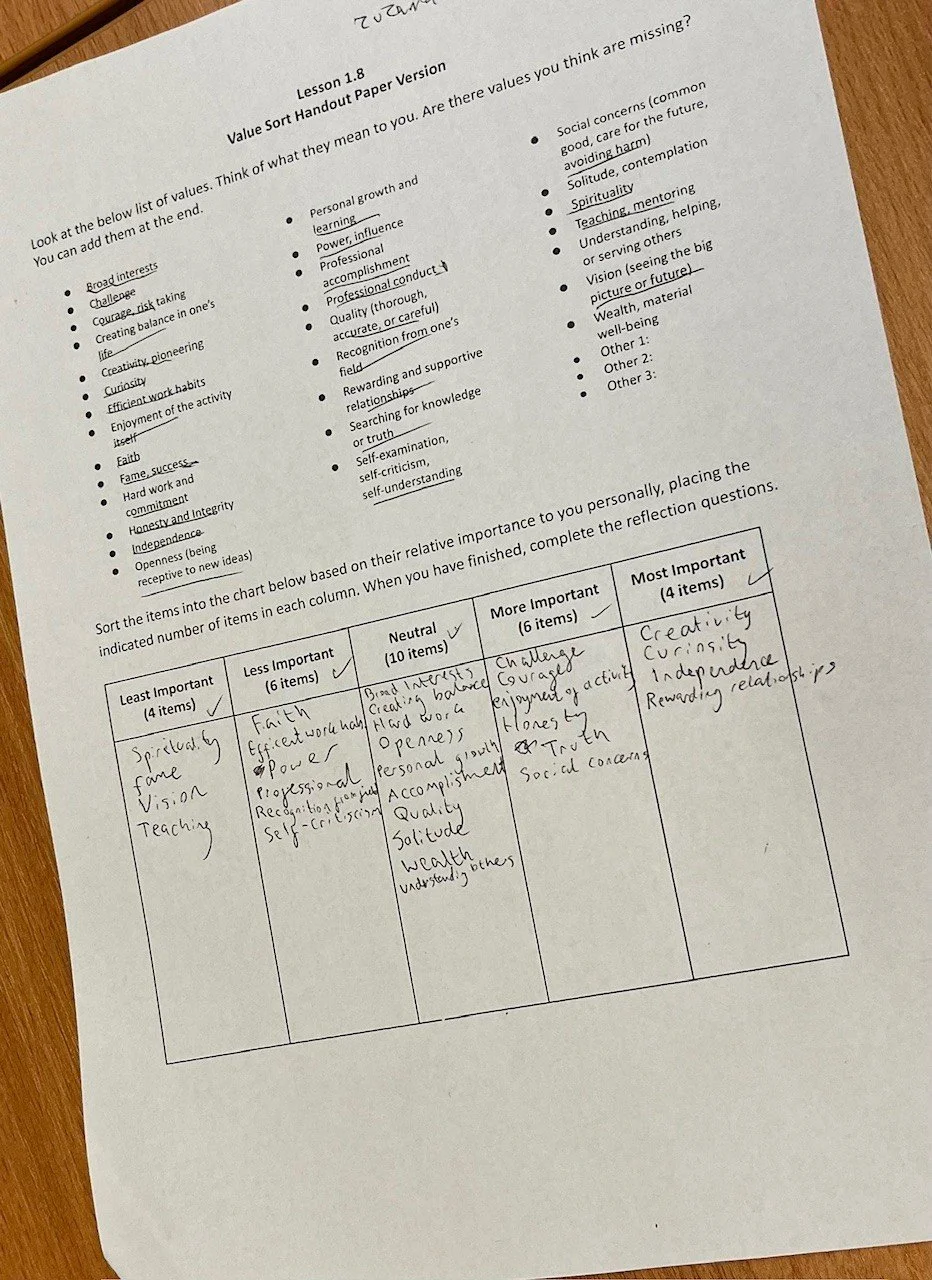

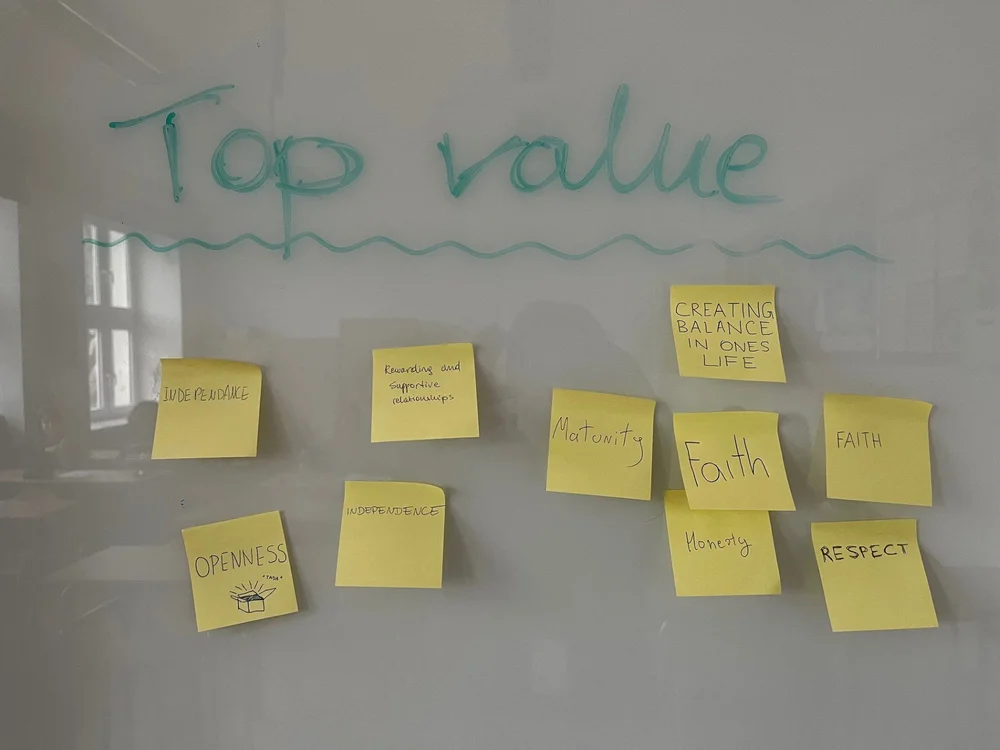

One memorable moment that stands out occurred during a value sort activity in lesson 1.8. I was eagerly anticipating this lesson because it aimed to help students identify which values guide their decisions and life choices. As we began the activity, we encountered technical difficulties accessing the online tool on mobile phones. Luckily, I had printed copies of the activity, and we proceeded with the paper version in the classroom and the students were to complete the online version at home.

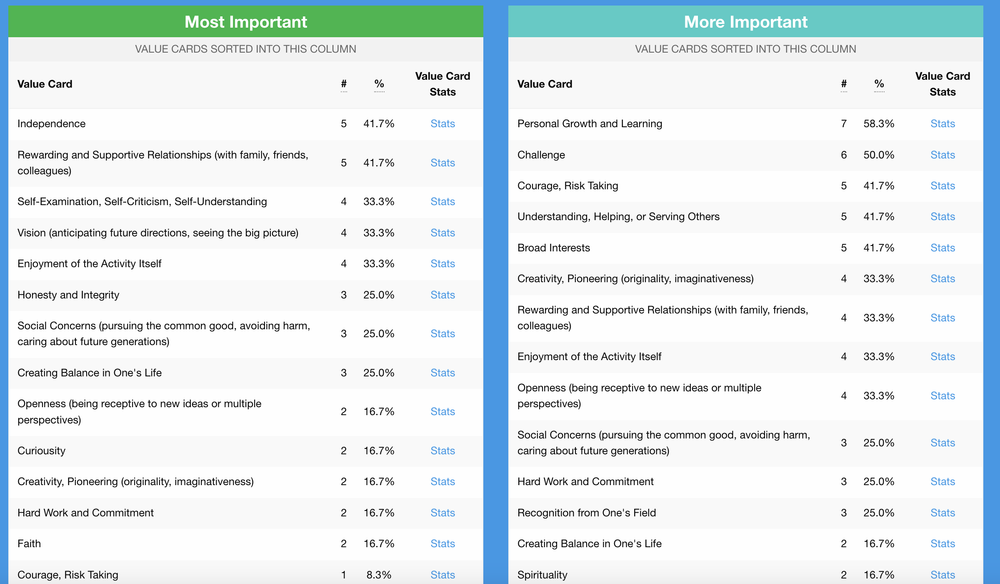

The next day, we reviewed the online results and group statistics, leading to a lively discussion about the difficulty of distinguishing the most important values from merely important ones. This activity revealed common values shared among the students and prompted a deeper conversation about the implications of different guiding principles on good work.

Revisiting the value sort results in lesson 3.2 a few months later allowed my students to reflect on their growth and evolving understanding of core values. Their enthusiasm during these discussions, which often spilled over into break times, was a joy to witness and highlighted the profound impact of the lessons.

What do you think are the main things your students are gaining or learning from their experiences with the lesson plans?

Through The Good Project lessons, my students are gaining a deeper appreciation for multiple perspectives and the importance of reflection. While they have always enjoyed discussions, these lessons present dilemmas and scenarios that compel them to consider the broader impact of their decisions on themselves, their peers, families, and the wider community. The "rings of responsibility" activity was particularly eye-opening, as it helped them realize the far-reaching consequences of their actions. This newfound awareness has fostered maturity and compassion, as they now approach dilemmas with a greater sense of ethical responsibility and empathy towards others.

What do you think other teachers should know before they begin teaching the lesson plans?

Teachers planning to work with The Good Project lesson plans should embrace the flexibility the plans offer. The lessons can be tailored to fit the needs and dynamics of their students, serving as inspiration for discussions and projects or as detailed guides with rich resources and alternative paths. It’s important to remember that initial reluctance or confusion from students is natural, but with time and encouragement, most will engage deeply with the dilemmas and activities. Teachers should also be prepared for the lessons to evolve beyond the initial plans, as new ideas and opportunities for deeper learning often arise during the process. The key is to create a supportive environment where students feel comfortable sharing their thoughts and reflections.

What are students learning that you feel will stick with them? What changes, if any, do you see in the way they approach certain choices or situations in school or in life?

One of the most impactful lessons my students are learning from The Good Project is the significance of ethical considerations in their decision-making processes. The discussions around values, ethical dilemmas, and the concept of "good work" have deeply influenced their understanding of what it means to act with integrity and responsibility. For instance, during our sessions on the 3Es—Excellent, Engaging, Ethical—they have understood the importance of striving for excellence not just academically, but in all aspects of their lives. They are also learning to engage with their schoolwork and to approach tasks with enthusiasm and dedication.

Moreover, the emphasis on reflection and the rings of responsibility has encouraged them to think about the broader impact of their actions. They now recognize that their decisions can have far-reaching effects, not just on their immediate surroundings but also on their community and beyond. This holistic approach to understanding consequences is something that I believe will stay with them long after they leave the classroom. It has equipped them with a framework to navigate complex situations thoughtfully and with empathy.

How do you view the relationship between what you teach in the classroom and your students’ overall development as people?

Since integrating The Good Project lessons into my teaching, I have observed a noticeable shift in the way my students approach both academic and personal decisions. They have become more deliberate and reflective, taking the time to weigh the ethical implications of their choices. For example, I’ve seen students who once rushed through assignments now taking the time to consider how their work can contribute positively to the classroom environment and their learning community.

In group projects, there is a newfound sense of collaboration and mutual respect. Students are more willing to listen to diverse perspectives and work towards solutions that are inclusive and fair. This change is particularly evident in their interactions during debates and discussions, where they exhibit greater patience and interest in understanding different viewpoints.

Why is it important for your learners to understand the meaning of “good work” for themselves, now and in the future?

Understanding the meaning of “good work” is crucial for students as they prepare to enter a rapidly changing job market. In the next 5-10 years, as they transition into their careers, the ability to do good work—work that is excellent, engaging, and ethical—will be essential for personal fulfilment and professional success. Teaching these values now helps them develop a strong moral compass and a sense of purpose. If students around the world are taught the value of good work, they will not only find joy and meaning in their careers but also serve as mentors and role models for future generations, fostering a culture of ethical and impactful work.

d huts or simple unfurnished brick houses. They were mostly small-scale farmers and labourers. At school the children learned many things, not just from books, but also by exploring, creating, imagining, tinkering and through dialogue and reflection. At the end of every school day the children cleaned the campus and made sure to keep their surroundings neat, colourful and beautiful.

d huts or simple unfurnished brick houses. They were mostly small-scale farmers and labourers. At school the children learned many things, not just from books, but also by exploring, creating, imagining, tinkering and through dialogue and reflection. At the end of every school day the children cleaned the campus and made sure to keep their surroundings neat, colourful and beautiful.

One day a man and a woman arrived at the gate of this remote school or free space. The man was Paul Salopek and he was accompanied by his walking partner Bhavita. Paul came walking all the way from Ethiopia and was on his way to Patagonia. He was curious to learn about people and places across the globe and write stories about them to share with the wide world. His long traverse was called ‘Out of Eden Walk’ and brought him to many unknown areas, just like the village where Loka’s school was emerging. Paul spent some days with Loka’s students, and the children were amazed by his journey. “Why walk by foot, why not use a car?” a puzzled student asked. Another wondered what Paul thought about Bihar – a state often depicted in mainstream media as dangerous, corrupt and poor. “Bihar is Beautiful” he said, “and the people are kind and welcoming.” Everybody at Loka was inspired by Paul’s story and presence, and his choice to give up everything and live a different life. Likewise, Loka had touched Paul’s heart, it seemed, as just over a month later he returned with a wonderful group of researchers from Project Zero, a research center at Harvard University. Every couple of years Paul met with them to have a conference about Out of Eden Learn (OOEL), an online platform for cultural exchange the researchers developed which is linked to Paul’s Walk.

One day a man and a woman arrived at the gate of this remote school or free space. The man was Paul Salopek and he was accompanied by his walking partner Bhavita. Paul came walking all the way from Ethiopia and was on his way to Patagonia. He was curious to learn about people and places across the globe and write stories about them to share with the wide world. His long traverse was called ‘Out of Eden Walk’ and brought him to many unknown areas, just like the village where Loka’s school was emerging. Paul spent some days with Loka’s students, and the children were amazed by his journey. “Why walk by foot, why not use a car?” a puzzled student asked. Another wondered what Paul thought about Bihar – a state often depicted in mainstream media as dangerous, corrupt and poor. “Bihar is Beautiful” he said, “and the people are kind and welcoming.” Everybody at Loka was inspired by Paul’s story and presence, and his choice to give up everything and live a different life. Likewise, Loka had touched Paul’s heart, it seemed, as just over a month later he returned with a wonderful group of researchers from Project Zero, a research center at Harvard University. Every couple of years Paul met with them to have a conference about Out of Eden Learn (OOEL), an online platform for cultural exchange the researchers developed which is linked to Paul’s Walk.

s of our economies, livelihoods, food security, health and quality of life worldwide.” (1) We also read an article about the decline of fireflies and monarch butterfly populations, specifically in Chicago. The students were struck by statements like, “Chicago and the surrounding area has already seen “significant” declines in its insect and bat population,” said Andrew Wetzler, managing director of the Nature Program at the Natural Resources Defense Council. Monarch butterflies — the orange and black butterflies that flutter around gardens and flowers in the spring and summer — and fireflies, a staple of many Chicagoans’ childhoods, are expected to be among the local insects that will be lost. Insects like butterflies and creatures like bats are pollinators, and plants need to be pollinated to produce food.

s of our economies, livelihoods, food security, health and quality of life worldwide.” (1) We also read an article about the decline of fireflies and monarch butterfly populations, specifically in Chicago. The students were struck by statements like, “Chicago and the surrounding area has already seen “significant” declines in its insect and bat population,” said Andrew Wetzler, managing director of the Nature Program at the Natural Resources Defense Council. Monarch butterflies — the orange and black butterflies that flutter around gardens and flowers in the spring and summer — and fireflies, a staple of many Chicagoans’ childhoods, are expected to be among the local insects that will be lost. Insects like butterflies and creatures like bats are pollinators, and plants need to be pollinated to produce food.

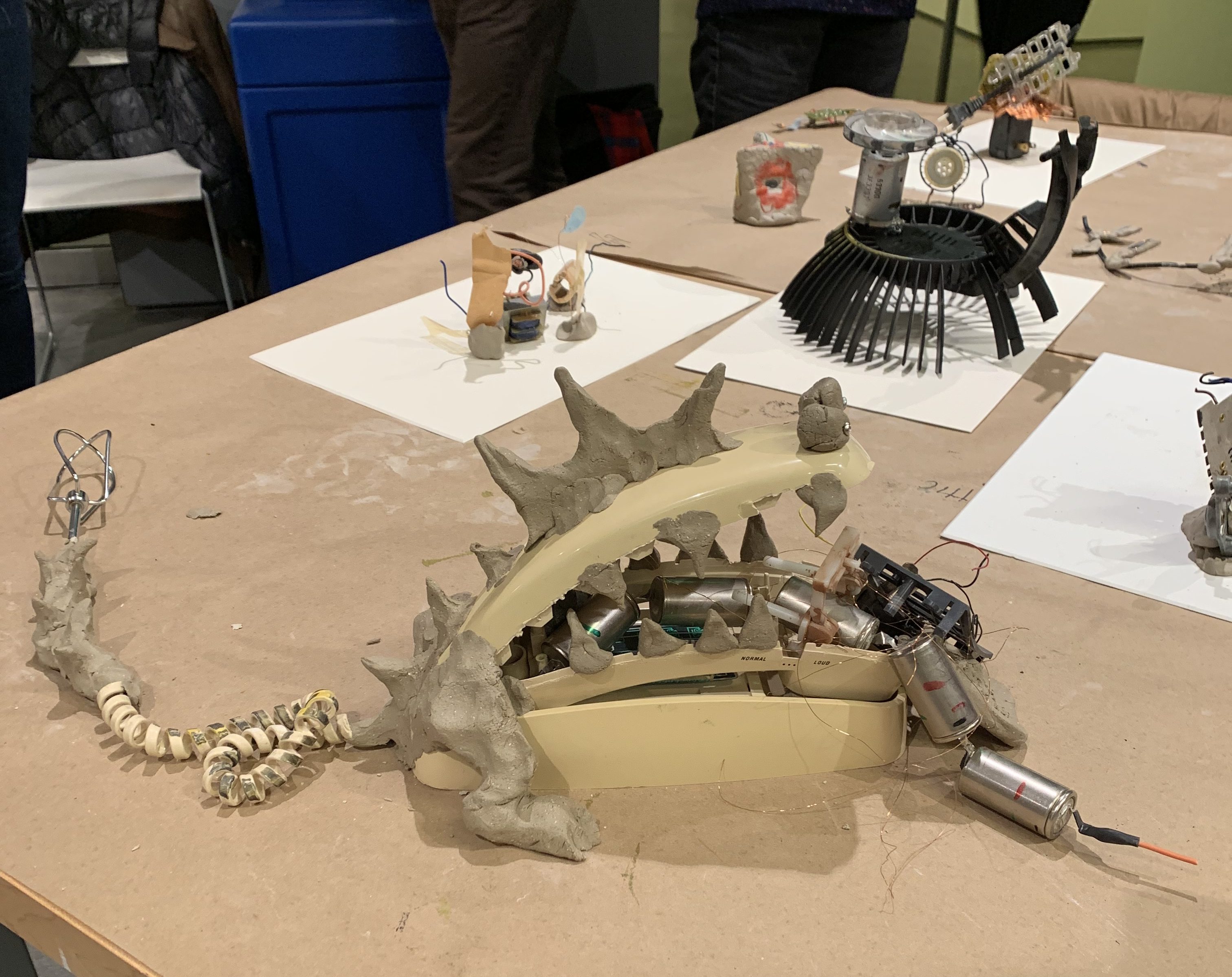

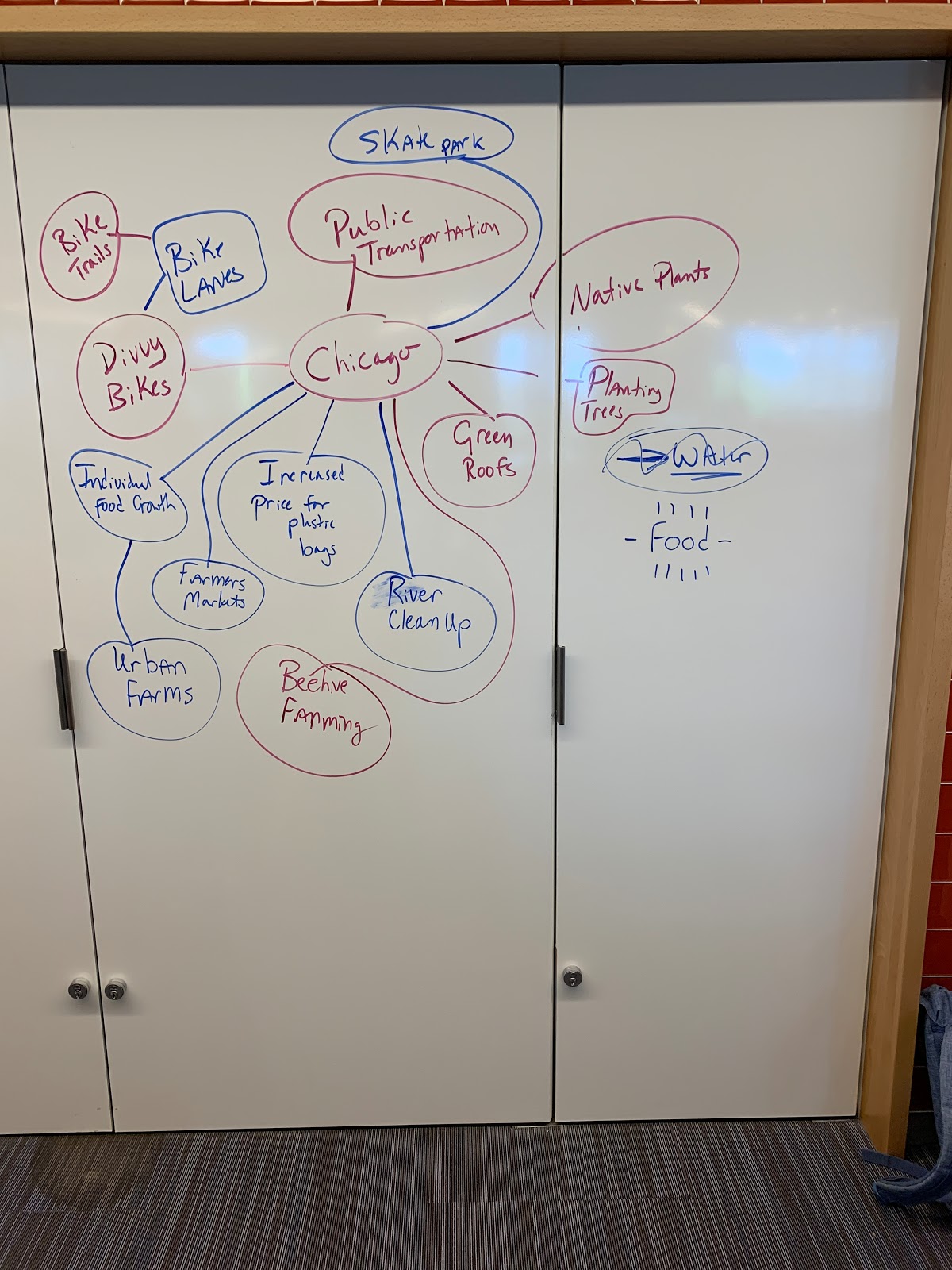

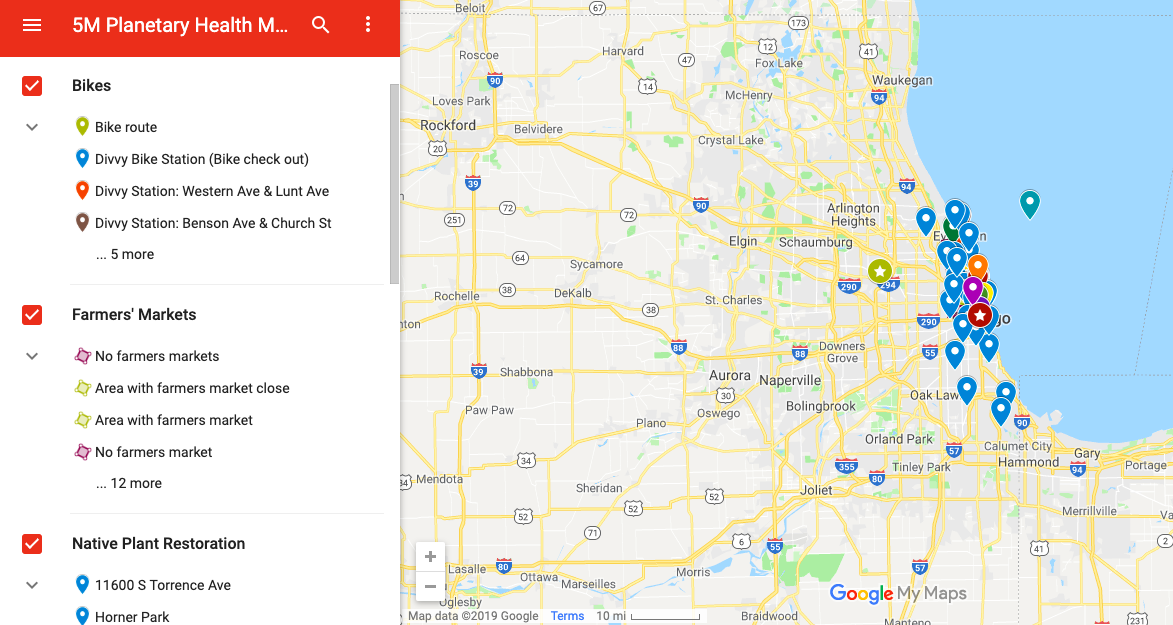

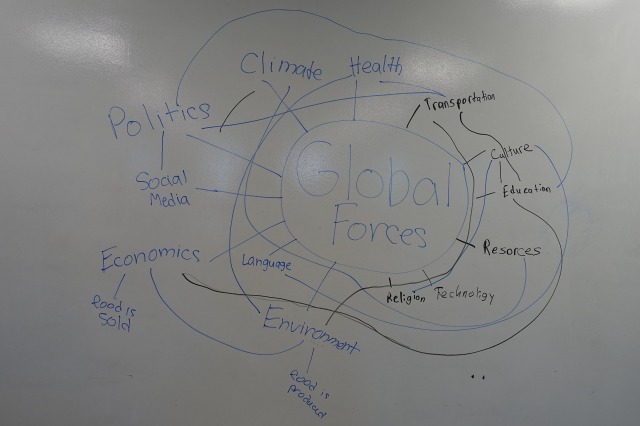

Students began by researching everything they could find that was happening at a local level, who was doing the work and what the issues were the Chicago community is trying to fix. They explored innovative ideas like robots being used to clean up the river. They discovered areas of the city that contained no farmer’s markets and were introduced to the concept of food deserts. They discovered the importance of planting native species in their own gardens and the impact that can have on pollinator populations.

Students began by researching everything they could find that was happening at a local level, who was doing the work and what the issues were the Chicago community is trying to fix. They explored innovative ideas like robots being used to clean up the river. They discovered areas of the city that contained no farmer’s markets and were introduced to the concept of food deserts. They discovered the importance of planting native species in their own gardens and the impact that can have on pollinator populations.

-

-

-

-

Support PZ's Reach