Luz Helena Cano es asistente de investigación de Out of Eden Learn y recientemente se graduó del programa de maestría de Artes en la Educación de la Escuela de Posgrados en Educación de la Universidad de Harvard.

El viernes 16 de julio, llevamos a cabo la primera sesión de preguntas y respuestas con Paul Salopek. Nos acompañaron maestros y estudiantes que han participado en la versión en español de nuestro programa y también aquellos que se han unido a nuestros recorridos de aprendizaje en inglés pero que pertenecen a colegios bilingües. El rango de edad de los estudiantes que nos acompañaron está entre los tres y medio y los quince años y se conectaron a este primer Google Hangout desde Bogotá (Colombia), Albacete, (España), dos grupos de Buenos Aires (Argentina) y una clase en la ciudad de México (México).

Paul nos acompañó desde Biskek (Kirguistán) o “el ombligo de Asia” como él lo llamó, mientras hace las preparaciones necesarias para seguir adelante con el recorrido hacia la India. En su presentación nos contó detalles sobre su caminata e invitó a su compañero y amigo de caminata, Aziz a saludarnos y contarnos sobre el cruce de Uzbekistán con Paul el año pasado. “Es bueno reconocer que esta caminata no es una caminata que hago solo, siempre ando caminando con amigos y colegas locales que no solo vienen siendo traductores sino que son mis ojos para ver el paisaje y la cultura local y regional”, dijo Paul.

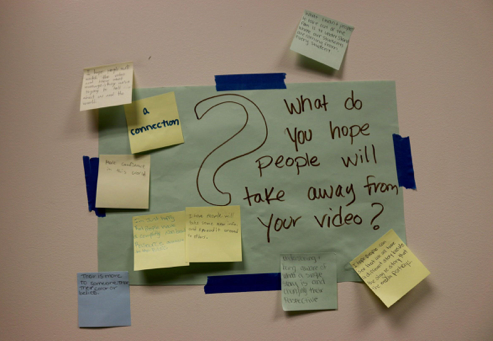

Muchas preguntas interesantes y profundas hicieron nuestros estudiantes a Paul. Por ejemplo, los alumnos de preescolar preguntaron por qué Paul no ha viajado a México o por qué hay guerras. También hubo preguntas por parte de estudiantes de secundaria sobre la familia de Paul, las barreras tanto físicas como emocionales y sociales que se ha encontrado en el camino y la formación de lazos con individuos o grupos en el camino.

Con respecto a esto último, Paul habló de que sus enlaces pueden parecer superficiales porque no pasa mucho tiempo con la gente, pero dijo que ha aprendido rápidamente a exponerse más fácilmente porque cuando va caminando a través de un “paisaje humano o una topografía humana”, se aprende rápidamente a exponer el corazón para hablar más honestamente, porque solo se tiene un tiempo breve para comunicar. “Las conexiones con la gente que me encuentro en el camino son muy significativas porque están muy marcadas por la generosidad y cada vez que alguien me saluda o me indica el rumbo o a tomar un café o un té es como una afirmación de este proyecto y se me pasa una palabra en la mente y es ¡sí!”

Aunque su recorrido a través de movimientos de refugiados y zonas de guerra en el Medio Oriente y Turquía lo ha puesto en peligro en ocasiones, esos incidentes son una minoría de los días de su viaje. Recalca que los recuerda muy bien porque son muy dramáticos pero insiste en que “lo más común es la bondad y la gentileza de la gente ordinaria que se encuentra en el camino”, sin importar la religión o la zona geográfica por la que pasa. “Me da esperanza, es una gentileza común a través de todas las culturas.”, dijo Paul.

Por otro lado, una estudiante le preguntó a Paul cómo hizo para tomar la decisión de hacer este recorrido y si fue un proceso largo o una decisión rápida. Su respuesta fue: “puedo decir que me he estado preparando para este viaje desde que niño, desde que cruce mi primera frontera entre México y los Estados Unidos. Fui a escuelas mexicanas, bailé bailes mexicanos y me enamoré al estilo mexicano, y lo que hizo eso fue abrir mi mente a cruzar fronteras no solo políticas sino de la experiencia humana y ese fue el impulso para hacer lo que estoy haciendo ahora. Yo diría que todas estas decisiones que tomamos en nuestras vidas están impulsadas muchas veces por impulsos que están un poco ocultos y a lo mejor muy antiguos también. Tomé la decisión en un par de meses.”

Otro elemento que descubrimos de la vida de Paul y que nos ayuda a entender su pasión por el recorrido que se encuentra haciendo fue la respuesta que dio cuando un estudiante le preguntó por lo que más le ha gustado de su caminata. Resulta que Paul nació en el desierto, al sur de California y en sus palabras nos dijo, “creo que algo de arena me entró a las venas porque me gustan muchísimo los desiertos y he pasado por muchos. En el desierto hay una increíble soledad; hay belleza muy sencilla, a veces una belleza muy dura. Pero el esfuerzo o nuestra tarea como reporteros e historiadores y también como humanos es encontrar ese tipo de belleza en todos los paisajes, hasta en las ciudades más grandes y frenéticas hay belleza, solo hay que encontrarla.” Un desierto que atravesará nuevamente en unos años será el de la frontera entre Estados Unidos y México. Ante la invitación de una estudiante de preescolar, Paul respondió: “cuando llegue a México en 5 años acompáñame a caminar”.

Entre otras maravillosas preguntas de nuestros estudiantes y las correspondientes bellas y sabias respuestas de Paul, este primer evento en español nos ayudará, como dijo Paul, “a unirnos todos, a tratar de comunicar mejor a través de las fronteras, comunicar a través de las culturas, comunicar a través del arte, de las historias que todos llevamos en el corazón, porque lo que yo he descubierto caminando de continente a continente es que todos llevamos historias que son muy comunes.”

Siga este enlace para ver el evento de preguntas y respuestas con Paul Salopek. ¡Es el inicio de una conversación que seguiremos!

Luz Helena Cano is an Out of Eden Learn research assistant and recently graduated master’s student from the Arts in Education program at the Harvard Graduate School of Education.

On Friday, June 16, we held the first Q&A session with Paul Salopek in Spanish. Teachers and students who have participated in the Spanish version of our program and also those who have joined our learning journeys in English but who come from bilingual schools attended the event. Classes joined the Hangout from Bogotá (Colombia), Albacete (España), Buenos Aires (Argentina), and Mexico City (Mexico). Youth participants ranged in age from 3-15 years old.

Paul joined us from Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan, or “the navel of Asia” as he calls it, while making the necessary preparations to continue with his journey towards India. He invited his friend and walking guide, Aziz, to greet us and tell us about his experience crossing Uzbekistan with Paul last year. “It’s good to recognize that this walk is not a walk that I do alone. I am always walking with friends and local colleagues who not only come to be translators but are my eyes to see the landscape and local and regional culture,” says Paul.

Our students asked Paul many interesting and profound questions. For example, preschoolers asked why Paul has not traveled to Mexico, and even why there are wars. Questions from high school students included questions about Paul’s family, the physical and emotional social barriers that he has encountered, and the bonds of friendship he has developed with individuals or groups along the way.

Regarding the latter, Paul said that these personal bonds may seem superficial because he does not spend much time with people, but that he has learned to open himself up more easily. When you are walking through a “human landscape or a human topography,” you quickly learn to open up the heart to speak more honestly, because you only have a brief time to communicate. “The connections with the people I meet on the way are very significant because they are marked by generosity and every time someone greets me or offers me a coffee or tea, it is an affirmation of this project, and a word passes through my mind and it is ‘yes!’”

Although Paul has encountered some danger along his route, such as walking through militarized zones in the Middle East and witnessing firsthand the Syrian refugee crisis and its impact on neighboring countries like Jordan and Turkey, dangerous incidents have been uncommon on his journey. He remembers them clearly because they were very dramatic but insists that “the most common thing is the kindness of ordinary people along the way,” regardless of the religion or geographical area through which he passes. “It gives me hope, it’s a common kindness across all cultures,” says Paul.

One student asked Paul how he made the decision to embark on this adventure and whether it was a long process or a quick decision. Paul responded: “I can say that I have been preparing for this trip since I was a child, since I crossed my first border between Mexico and the United States. I went to Mexican schools, I danced Mexican dances and I fell in love with the Mexican style, and what that did was open my mind to cross borders, not only political, but also those of the human experience. And that gave me the impulse to do what I am doing now. I would say that all the decisions we make in our lives are driven many times by impulses that are a bit hidden and maybe very old too. I made the decision in a couple of months.”

Another element that we discovered about Paul’s life that helps us to understand his passion for his journey was the response he gave when a student asked him what he liked most about his walk. It turns out that Paul was born in the desert, to the south of California. He told us, “I think that some sand entered my veins because I like the deserts very much and I have passed across many. In the desert there is incredible solitude, but there is also very simple beauty, which is sometimes a very hard beauty. But the effort, or our task as reporters and historians and also as humans, is to find that kind of beauty in all landscapes. Even in the biggest and frantic cities, there is beauty. You just have to find it.” A desert that Paul will cross again in a few years will be that of the border between the United States and Mexico. At the invitation of a preschool student, Paul responded, “When I arrive in Mexico in 5 years time, walk with me.”

Besides the wonderful questions from our students and the correspondingly beautiful and wise answers from Paul, this first event in Spanish will help, as Paul says, “to unite us all, to try to communicate better across borders, communicate through cultures, communicate through art the stories we all carry in our hearts. Because what I’ve discovered by walking from continent to continent is that we all carry stories that are common to all of us.”

Follow this link to see the complete first Q&A hangout with Paul Salopek. It is the beginning of a conversation that we hope to continue!

-

-

-

-

Support PZ's Reach