This piece stems from research carried out by Liz Dawes Duraisingh, Emi Kane, and Sarah Sheya, with contributions from the rest of the Out of Eden Learn team. All graphics are by Sarah Sheya.

As we explained in a recent blog post, the research agenda of Out of Eden Learn is intimately connected to the real-world implementation of our program. We are doing design-based research in which “the central goals of designing learning environments and developing theories or ‘prototheories’ of learning are intertwined.” (1) Part of this work consists of systematically analyzing data related to the project–such as student work, comments, and survey responses, and student and teacher interviews–to discern emergent patterns and themes that can inform both theory and practice.

One of our research strands involves investigating the opportunities and challenges associated with engaging young people online around the topic of human migration. This blog post, the first in a series of two, revisits the emergent, empirically-grounded pedagogic framework for changing the conversation around migration that we previously shared. The intent is to share some details of our ongoing research and design process and to present and explain a slightly revised version of our framework. A follow-up piece will describe changes we made to the Stories of Human Migration curriculum in light of our research and development of the framework.

First, here is a brief description of our research process. We used spreadsheets and coding software to analyze our data, which came from three principal sources, all collected in the fall of 2016/spring of 2017:

- Student work and comments. We looked at student work from two walking parties (online learning groups) involving 140 students from seven different countries, including five different US states. Their learning contexts included history, social studies, journalism, photography, and English language classes. We exported all pieces of student work and associated student comments from our platform.

- Student survey responses. 65 students completed an optional online survey about their experiences with the Stories of Human Migration learning journey shortly after completing the curriculum. Students were asked to reflect, for example, on what they had learned, appreciated, or found challenging about the learning journey.

- Educator interviews. We conducted video chat interviews with 14 educators who had experience using the curriculum in a range of subject areas and with varied student populations. We looked for signs of resonance with student perspectives, as well as important information regarding how educators were interpreting and implementing the curriculum within their different teaching contexts.

The three team members working on this strand of research (Emi Kane, Sarah Sheya, and myself) then engaged in “open-coding” of the student data–that is, we took careful note of what we saw students doing (e.g., making personal connections to other people’s migration stories or critically analyzing news articles) and saying (e.g., stating that they had learned the importance of trying to take on other people’s perspectives or that they now felt motivated to follow migration in the news more carefully). What we noticed in the data was certainly informed by our aspirations for the curriculum; however, we very much wanted to learn from the students about the possibilities of the space rather than merely assess the extent to which they did or said things we already hoped for or anticipated.

This initial analysis generated a wide range of ideas. In fact, we started by identifying 44 different themes, which we then consolidated and revised into a much leaner model or framework: the colorful kaleidoscope-inspired graphic we presented on this blog last September. This diagram was organized around three core dimensions related to engaging young people around the topic of human migration: respectful curiosity and engagement, nuanced understanding, and critical awareness including self-awareness.

We have since revisited the student work, survey responses, and educator interviews to ensure the robustness of the framework and its ‘fit’ with our data. As part of that process, the three of us independently analyzed the same 40 pieces of student work to make sure we were being consistent in terms of how we were interpreting the data and applying the framework. For the most part, the original framework feels like a solid fit. However, we have made some small adjustments, as reflected in the updated visual below:

You can download a high resolution printable version of the framework here.

Below is a summary of the changes we have made.

In the NUANCED UNDERSTANDING cluster, we have tweaked the three components to differentiate more carefully among the kinds of understandings we have seen students start to develop, but which could collectively be summed up as “migration is complicated and diverse”.

This first triangle is intended to represent a broad range of understandings related to the kinds of push/pull factors involved in human migration. We found that the richest student work took account of individual human agency and bigger forces at play when explaining particular migration stories. Our previous wording focused more on “the interplay” of structural forces and individual stories: while students will ideally consider how the individual and the structural interact, this focus felt rather specific for the general orienting purposes of this framework.

The second triangle points to the wide diversity of migration experiences across humanity, as shaped by different historical, geographic, and political contexts. Our analysis suggests that this aspect of understanding is enhanced when peers from different contexts share stories with one another: students commented in the surveys, for instance, that they had learned from reading different posts that migration experiences can be extremely varied. At the same time, students may notice unexpected resonances across migration stories, especially given that migration is a fundamental and ongoing aspect of the story of our human species.

The second triangle points to the wide diversity of migration experiences across humanity, as shaped by different historical, geographic, and political contexts. Our analysis suggests that this aspect of understanding is enhanced when peers from different contexts share stories with one another: students commented in the surveys, for instance, that they had learned from reading different posts that migration experiences can be extremely varied. At the same time, students may notice unexpected resonances across migration stories, especially given that migration is a fundamental and ongoing aspect of the story of our human species.

The third triangle points to the complexity of how individuals experience migration. Individual migration stories can involve a dynamic blend, for example, of loss and gain, fear and hope, and connection to the old as well as adaptation to the new. We removed the word ‘diversity’ from this triangle in an attempt to distinguish between difference or commonality and complexity in the triangles.

The CRITICAL AWARENESS cluster remains largely unchanged.

The aspect of critical awareness captured in this triangle carries over from the initial diagram given the role of news media and other content in shaping contemporary perceptions of migration, at times in polarizing or simplistic ways.

Perspective-taking also holds up as a crucial aspect of critical awareness. However, we have shifted our wording to emphasize the importance of students valuing opportunities to try to take on and understand other people’s perspectives, while also being aware that perspective-taking is not a simple task. People’s perspectives are shaped by a complex and shifting combination of factors including personal background, life experiences, social contexts, and exposure to different kinds of narratives and perspectives.

The content of the third triangle, meanwhile, has been conceptually expanded. The new wording is intended to capture students’ ability and willingness to reflect on their own relationship to and understanding of migration, and how their relationship and thinking may be evolving or developing over time, perhaps because of an experience such as Out of Eden Learn. They recognize that their own perceptions of migration are at least in part shaped by their own identities, backgrounds, and life experiences.

The content of the third triangle, meanwhile, has been conceptually expanded. The new wording is intended to capture students’ ability and willingness to reflect on their own relationship to and understanding of migration, and how their relationship and thinking may be evolving or developing over time, perhaps because of an experience such as Out of Eden Learn. They recognize that their own perceptions of migration are at least in part shaped by their own identities, backgrounds, and life experiences.

For the final cluster, CURIOSITY AND ENGAGEMENT, we have taken the word “respectful” out of the heading –not because we no longer value it but because there was a risk of us privileging this quality over other important qualities such as bravery or authenticity, which similarly feature in the Out of Eden Learn Community Guidelines. In addition, we have made some adjustments to the components in the cluster so that they capture the bigger aspects of what students were doing and saying in our data, rather than more specific actions or indicators.

This wording replaces two previous aspects: “honors and connects to others” and “asks thoughtful questions; initiates discussion”. These two previous aspects certainly captured what we observed students doing in our data but we felt they were indicative of something more important. Our choice of the phrase “Responds with sensitivity” intends to convey being attuned and attentive to what others are saying, as well as responding thoughtfully and with respect. Importantly, it invokes the act of listening.

This wording replaces two previous aspects: “honors and connects to others” and “asks thoughtful questions; initiates discussion”. These two previous aspects certainly captured what we observed students doing in our data but we felt they were indicative of something more important. Our choice of the phrase “Responds with sensitivity” intends to convey being attuned and attentive to what others are saying, as well as responding thoughtfully and with respect. Importantly, it invokes the act of listening.

This component is about more than making connections between one’s own life or family story and those of other people, though that is certainly important and to be encouraged. It is about feeling part of or included in the bigger and unfolding story of human migration, which in one way or another ultimately implicates us all.

This final aspect, which points to future-looking shifts in motivation or engagement, remains the same. We define “engagement” broadly to include things such as keeping abreast of current news stories involving migration, making an effort to be thoughtful and supportive of newcomers, or advocating and/or volunteering for organizations that work with or are run by refugee communities.

Meanwhile, the core design principles of Out of Eden Learn, which we believe help to foster these dimensions of learning, continue to be threaded through the center of the diagram: slowing down, sharing stories, making connections.

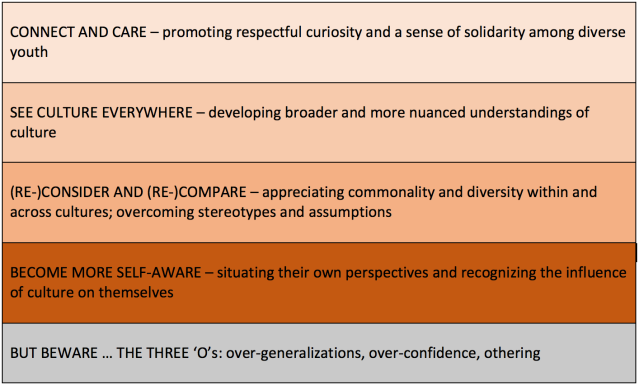

Finally, it is worth noting that while the framework is written in terms of positives, our analysis also picked up on what could be deemed counter-examples for each of the categories. However, given the challenge of determining student intent and/or assessing what was perhaps missing from their posts, as researchers we often found it hard to agree as to whether individual pieces were somehow deficient or problematic. Given that the goal of this framework is to orient and provide ideas to educators as they seek to engage young people around the topic of migration, we think it is useful to summarize a few potential pitfalls to look for when using this guide. Here, we noticed great synchronicity with another Out of Eden Learn research strand on young people’s thinking about culture(s): we are therefore sharing language adapted from a recent blog post on that topic, regarding the “Three O’s”:

OVER-GENERALIZATIONS. Students can at times default to single stories, make sweeping or vague statements about their own or other people’s migration stories, or gloss over similarities and/or differences among different types of migration and different individual experiences.

OVERCONFIDENCE. Relatedly, students can lack appropriate humility about their own knowledge, over-assert themselves as representatives of particular migration stories, or assume their own experiences and/or perspectives as the default. Some students leave Out of Eden Learn appearing to overstate how much they now know about migration and how well they understand or can take on the perspective of people who have had different experiences to their own.

OTHERING. We have found that some students tend to romanticize or exotify other people’s lives or circumstances, or make them an object of pity in uncritical and even disrespectful ways–presumably unintentionally. We have found this to be particularly true when students who feel settled in one place talk about people who are forced to migrate primarily because of push factors such as war, violence, or economic hardship. Finding the balance between thoughtful compassion and inappropriate pity is not easy, but paying close attention to context, tone, and language can help.

It is important that we offer young people opportunities to engage in meaningful and thoughtful ways around the topic of human migration. As this post demonstrates, we are still learning about how to facilitate such opportunities, and anticipate our work involving further iterative loops of research to design and back again. Part 2 of this series will explain some tweaks we have made to our own curriculum and further changes in the works as we attempt to promote the capacities outlined in our kaleidoscope diagram and to circumnavigate the “Three O’s.”

(1) The Design-Based Research Collective (2002). Design-Based Research: An Emerging Paradigm for Educational Inquiry. Educational Researcher 32 (1) pp. 5-8.

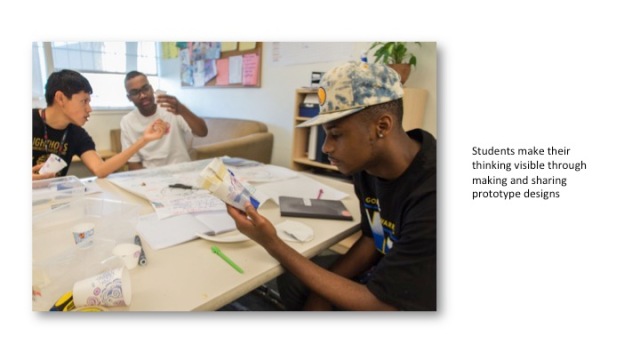

program evaluation (as Bare notes) or to referencing key historical moments (as in the case of the tribal elders), but also to broader thoughts about education. Too often, the values that guide the creation of educational assessment and documentation tools are far removed from the teaching and learning environments in which they’re used, and might even be mysterious to the practitioners that use them. Even more often, learners are completely left out of the practices of documentation and assessment, and framed as subjects of research rather than as participants in the process. This phenomenon seems to run counter to notions of

program evaluation (as Bare notes) or to referencing key historical moments (as in the case of the tribal elders), but also to broader thoughts about education. Too often, the values that guide the creation of educational assessment and documentation tools are far removed from the teaching and learning environments in which they’re used, and might even be mysterious to the practitioners that use them. Even more often, learners are completely left out of the practices of documentation and assessment, and framed as subjects of research rather than as participants in the process. This phenomenon seems to run counter to notions of  This diagram is intended to evoke the metaphor of a kaleidoscope: the various parts are interconnected and can come together as well as expand or recombine in different ways. The diagram is color-coded according to three broad aspects of learning. The pink shapes represent the affective or attitudinal qualities we hope to promote among young people as they engage around the topic of human migration; the blue shapes represent the kinds of substantive understandings we want them to develop; the green shapes convey the dimensions of critical awareness that we believe to be important for navigating this topic in insightful and sensitive ways. At the center of the diagram and stretching across it are the core design principles of the Out of Eden Learn model, which we believe help to foster the attitudes, understandings, and capacities identified.

This diagram is intended to evoke the metaphor of a kaleidoscope: the various parts are interconnected and can come together as well as expand or recombine in different ways. The diagram is color-coded according to three broad aspects of learning. The pink shapes represent the affective or attitudinal qualities we hope to promote among young people as they engage around the topic of human migration; the blue shapes represent the kinds of substantive understandings we want them to develop; the green shapes convey the dimensions of critical awareness that we believe to be important for navigating this topic in insightful and sensitive ways. At the center of the diagram and stretching across it are the core design principles of the Out of Eden Learn model, which we believe help to foster the attitudes, understandings, and capacities identified.

Since the start of this initiative, cohort members have been asked to give feedback to each other about their developing projects via an online platform. This platform created opportunities for cohort participants to view and comment on each others’ project documentation and online reflections. Cohort schools also presented their work to each other and to members of the public through exhibitions that showcased documentation of their school innovation projects and articulated key learnings, questions, and puzzles they encountered in that work.

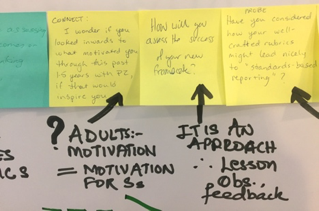

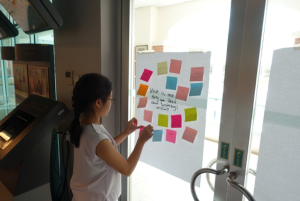

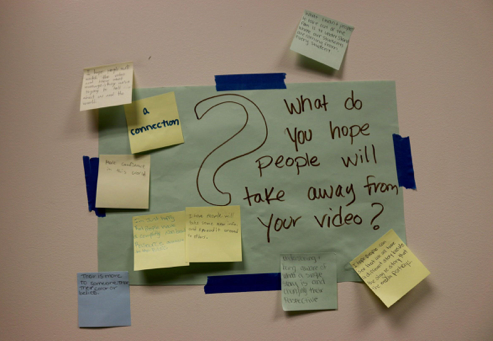

Since the start of this initiative, cohort members have been asked to give feedback to each other about their developing projects via an online platform. This platform created opportunities for cohort participants to view and comment on each others’ project documentation and online reflections. Cohort schools also presented their work to each other and to members of the public through exhibitions that showcased documentation of their school innovation projects and articulated key learnings, questions, and puzzles they encountered in that work. When using the Dialogue Toolkit in face-to-face communications, we’ve seen our cohort members make more explicit invitations for dialogue and critique around their work. At a recent exhibition, one school articulated their questions for feedback on a piece of chart paper, asking audience members to focus their comments on those questions. In this way, the school was able to walk away with specific feedback that was targeted toward helping them move forward. The Dialogue Toolkit prompts also helped educators notice recurrences of similar audience questions, and to move beyond conversations about the practicalities of implementation toward deeper discussions about the merits of their work.

When using the Dialogue Toolkit in face-to-face communications, we’ve seen our cohort members make more explicit invitations for dialogue and critique around their work. At a recent exhibition, one school articulated their questions for feedback on a piece of chart paper, asking audience members to focus their comments on those questions. In this way, the school was able to walk away with specific feedback that was targeted toward helping them move forward. The Dialogue Toolkit prompts also helped educators notice recurrences of similar audience questions, and to move beyond conversations about the practicalities of implementation toward deeper discussions about the merits of their work.

-

-

-

Support PZ's Reach